The three models for data management for smart grids in Europe:

The discussion about digitalization, big data and data management has finally reached the electricity sector. Today, we want to focus on the latter issue again, data management. Last week, we introduced the data management models that are currently discussed in Europe and North America to manage data from smart metering. Today, we want to dive deeper into this topic and discuss the strength and weaknesses of these models from an economic/institutional perspective.

Previously on this blog:

- “DSO as market facilitator”: The DSO (distribution system operator) becomes responsible for data collection, storage and allocation. These tasks are usually summed up under the headline of data management or meter data management.

- “Central Data HUB – Third Party as market facilitator” – one central data hub has the national monopoly for data management and is regulated

- “Data Access Point Manager (DAM)” – decentralized market-based approach with a standardized connection point between the meter and the eligible parties. This connection point is the DAM.

For a more comprehensive overview take a look here.

The criteria for the evaluation of the data management models

Now let’s analyze these three models in greater detail by using 7 different criteria. This list of criteria is not exhaustive and the analysis below shall provide a first basis for discussion. We are fully aware that the qualitative arguments are not final and can be challenged. And, to be honest, that is what we are striving for: Challenge our arguments and convince us of your opinion! We hope that you pick up the discussion and help us develop the evaluation further.

Having said this, let’s briefly take a look at the criteria that we applied to evaluate the different data management models discussed in Europe:

- data access

- provider and technology neutrality

- coordination

- costs

- synergies

- innovation

- regulation

Data Access: The key question here is whether we can expect the responsible party for data management not to discriminate certain parties that need access to the data. This refers to both, the access to the data management system as well as the daily operation.

Provider and technology neutrality: The operator that is responsible for the data management is likely to be responsible for the data infrastructure as well. We know from the telecommunication sector that provider and technology neutrality (i.e. every provider has the same chance to be the provider of choice for the management system, independent from the technology it uses, e.g. powerline communication vs. fiber etc.) are important to reduce costs of infrastructure provision. Therefore, the data management model needs to secure both, provider and technology neutrality.

Coordination: Here, we need to take a look at how the different models influence the vertical coordination within the electricity supply chain, especially between network operator and network users. This coordination issue is at the heart of RES (renewable electricity supply) integration and smart grids. Therefore, we discuss this issue with respect to data management in a research paper available here. Besides vertical coordination, the coordination on the horizontal level is important, e.g. among market parties or between the network operators and different data management systems using the same data management model.

Costs: Obviously, costs are important. Here, we want to take a look at the potential for economies of scale that can be exploited by each model. Additionally, we suggest the provider of the data management model should invest efficiently to reduce the costs of the system for its customers. We can expect competition to increase efficiency, which is why efficient investment is not so much an issue for market-based models. However, as soon as we discuss regulated models, efficiency depends on regulation and the incentives given to the operator of the data management system. We will see later on that this is an important issue.

Synergies: Data is not only available form smart metering, but also from the network infrastructure, other energies (e.g. gas) and markets. Furthermore, ICT (information and communication technology) infrastructure is required for data management in smart grids as well as for other purposes (e.g. telecommunication). How do the different models pick up this potential for synergies?

Innovation: Smart grids are still in the introduction phase. Therefore, the future development in this context is highly uncertain, which in turn requires that the data management model is capable to adapt to these changes and that it can facilitate innovation. Again, this is especially, but not only, an issue for the regulated models.

Regulation: Some models might require regulation, either a new regulation due to the development of a new role for data management, or an adaptation of existing regulation e.g. of the network operators. Even if the model is directly regulated, standardization is likely to become necessary, especially if we want competition to evolve.

The Results: The institutional evaluation of data management models in smart grids

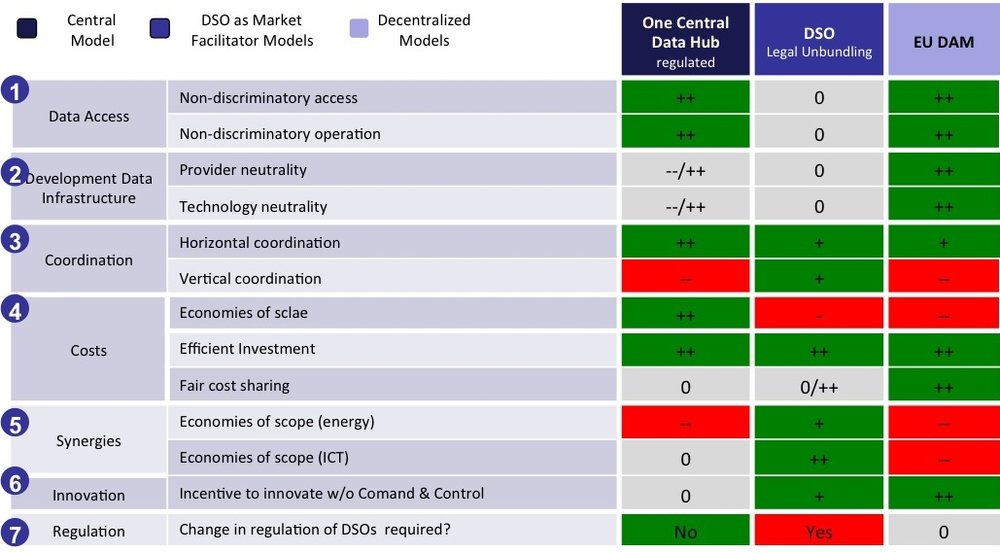

The following figure gives an overview of our first evaluation of the three European models for data management. It shows a qualitative indication of how the different models perform with regard to our seven criteria. The performance is described on a scale ranging from — (poor) to ++ (very good).

Figure 1: Evaluation Data Management Models Smart Grid: First Results

We cannot provide a detailed description of all indicators for each model here. Rather, we will briefly discuss the three models with respect to their key strength and weaknesses. Again, please keep in mind that this very general evaluation shall only serve as a basis for discussion. We do not consider this evaluation to be final nor to provide the only right answer. Actually, the discussion is quite complex; so we invite everybody to give us their (possibly contrary) view on this topic in the comment form below.

DSO as market facilitator

The “DSO as market facilitator” concept delegates the responsibility for data management to the legally unbundled DSO (for further information on this model take a look at this post). Securing equal access for all participants is the key challenge for this model, as this depends heavily on the effectiveness of (existing) regulatory prescriptions on the behavior of the network operator. The incentive for the DSO not to discriminate against other parties that participate or want to participate in the data management can only be secured, if the DSO does not use the data except for network operation. As soon as the DSO becomes active in the commercial part of the supply chain, e.g. by providing services to consumers based on the data from the data management system, the DSO has an incentive to discriminate against other parties to protect its market share. The same is true if the DSO has (strong) ties to other companies from the competitive parts of the electricity supply chain (e.g. retail, generation) as is the rule in Europe where DSOs are often part of a larger holding that owns retail and generation companies as well (legal unbundling). If these sister companies provide competitive services based on the data received from the DSO, the DSO might have an incentive to limit the access to data of potential competitors of the sister companies to secure the market share of the sister company. While this behavior should be permitted via legal unbundling, there is still some uncertainty whether legal unbundling can secure neutrality in case that the DSO becomes involved with tasks like data management.

Provider and technology neutrality might be at stake for this model as well, as a DSO might have an interest in building up its infrastructure for data management based on its own assets, e.g. using powerline communications, while this solution might not be the most efficient in terms of costs and a future proof solution (for further information on this issue see for example the OECD, 2009: 20)

Concerning the efficient operation, the DSO model might gain benefits from economies of scope and scale depending on the total number of DSOs in an electricity system. For example, if every DSO in Germany (currently there are more than 800 DSOs) takes responsibility for data management in its network area, then economies of scale will be very low, at least compared to a situation with just one data management system for the whole of Germany. On the contrary, a system with one DSO, like it is currently running in France, might result in very high economies of scale.

Another strength of the DSO model compared to the other models is the higher level of vertical coordination in smart systems , which goes down the electricity supply chain. The key question concerning vertical coordination is how we secure that the DSOs exchange information with all market participants to increase the overall efficiency of the electricity system. While this information exchange used to be operated internally in integrated utilities (with networks, retail and generation being part of one single company), this coordination now needs to be facilitated by market signals, which is a challenging task. If the DSO is in charge of data management, he is directly involved in data exchange with all market participants, which might give the DSO a high degree of transparency and thereby might increase efficiency. The potential is there, but strongly depends on the DSO’s ability to have access to the data within the data management system, which might be prohibited due to unbundling requirements.

Horizontal coordination might become a challenge within the DSO model as well. There are already strong concerns with respect to the interoperability of the decentralized data management systems developed by the DSOs today. These concerns are based on the current experience (especially of the regulator and the TSOs who both require data from the DSOs to fulfill their legal obligations) with the independent systems used by the DSOs to manage their networks. These network management tools differ on a very basic level, e.g. with respect to the granularity of information (15 Minutes vs. hourly-approach). Therefore, the question is raised whether a DSO based data management model will secure interoperability of the data management systems between the different DSOs. Such divergences can (intentionally or unintentionally) significantly hinder the development of services on the basis of such data. Regulation would need to ensure interoperability.

To combine the responsibility for the electricity networks and data management in one entity might result in efficient investment in and operation of these two infrastructures. It is likely that the operation of data management, including the investment into the necessary infrastructure will be efficient in economic terms given that the DSO is responsible for the data management. The infrastructure for data management can then be coupled with existing grid data systems. Such a single infrastructure reduces investment costs compared to a case of a DSO data infrastructure to maintain grid stability and a separate infrastructure for the data exchange between market parties. To avoid double investment, the “DSO as market facilitator” model provides a solution out of one hand, which increases efficiency. However, the DSO might not have the incentive to make use of the existing ICT infrastructure that is owned by a third party. This could result in double investments by the DSO to make use of its own telecommunication infrastructure. These investment decisions are strongly influenced by the regulation system and how the DSO can recover costs.

A further advantage of this DSO-centered approach is that it builds upon the current responsibilities and that the regulation in the electricity sector only needs adaptations. There is no need for regulatory supervision of additional parties. The investments made by DSOs for the data infrastructure could easily be regulated by the existing regulation scheme, which incentivizes efficiency and cost reduction. Thereby, efficient investment into the necessary infrastructure for data management could easily be implemented through regulation.

Independent central data hub (CDH)

The CDH approach is based on the separation of data management from all other areas of the electricity supply chain. Therefore, there is no incentive for the CDH to either restrict access to market entrants or to discriminate against other parties in the daily operation of the data management. However, this is only true if the CDH is neither related to the incumbent players in the electricity supply chain nor to those businesses, which enter the electricity market based on the new business opportunities created by data management. Therefore, the CDH should not only be separated from the incumbent electricity companies, but from all businesses, which might be related to smart grids in general. Otherwise, equal access and non-discrimination might not be secured (without regulation) by this concept. The containment that the CDH should not be related to any business in the realm of smart grids (or regulated) is required to secure provider and technology neutrality as well. Let’s assume a case in which a company from the telecommunication sector operates the CDH: this would be an option for a separate operation from the electricity supply chain. In this case, the CDH could have an incentive to apply the technology from its telecommunication division to increase own profits, independent from the question whether this technology is the most suitable in the specific case. Given that the CDH is an integrated part of another than the electricity supply chain, the regulator would need to secure provider and technology neutrality, e.g. through standardization of the ICT infrastructure and the definition of tendering rules.

Concerning the efficient operation of data management the CDH could be beneficial. For example, a CDH could be responsible for managing data exchange for several areas, which is likely to result in economies of scale and scope. However, compared to integrated solutions, like the “DSO as market facilitator model”, the CDH has certain detriments with respect to economies of scope to network management due to higher transaction costs for coordination with the electricity supply chain. Whether the gains for efficient operation outweigh the losses from coordination with the network operation cannot be answered from today’s perspective and this issue needs further investigation.

For the CDH concept, the degree of horizontal coordination throughout the total electricity system, especially between different regional applications of data management in smart grids, depends on two aspects. First, the number of different CDHs in one electricity system has a strong influence on coordination aspects. In the case that the total number of different CDHs in one electricity system is low, e.g. because one CDH is responsible for data management of different regions, then horizontal coordination can reach a high level (as can be seen in the Norway, Denmark or Belgium). With a higher degree of decentralization of CDHs, the level of horizontal coordination is likely to decrease. Second, the level of horizontal coordination in a system based on different CDHs depends on the degree of standardization in the system. Standardization would then need to be supervised by the regulator to ensure a high degree of coordination between different data hubs.

The CDH seems to be an appropriate approach to secure an efficient investment into the necessary infrastructure for the data management to maintain its profits. Either competition or, in case that one CDH operates a nation-wide data hub, regulation should secure the feasibility of the data hubs investments.

The concept of one single CDH in one country is likely to increase the tasks of the regulator, especially if the CDH is related to other businesses outside the electricity supply chain that might have an economic interest in smart systems. Otherwise, in a system with competing CDHs, the standardization for the coordination between different CDHs and the efficiency of its investments will require the attention of the regulator.

Data-Access Point Managers (DAM)

The market-based approach with different DAMs ensures a high degree of open access and non-discrimination as every individual consumer has the free choice to select a specific DAM. Furthermore, provider and technology neutrality can easily be fulfilled by this concept as the market offers each type of technology. The regulator then needs to define standards for these solutions to ensure the interoperability of the overall system. Without regulatory intervention, the level of vertical and horizontal coordination in a system with many different DAMs is likely to be very low. The potential for economies of scale is high in a market for data management, but it is less certain that this potential will be exploited given a decentralized DAM approach, at least compared to the concepts with one regulated data hub.

A clear advantage of the DAM approach is that it might result in a high efficiency of investment, which is assumed to result in a competitive market. Furthermore, in this competitive environment the costs will be directly linked to the consumers who gain the profits from the system, as each consumer has to pay for his individual DAM. Though the DAM concept focuses on a competitive solution, the need for regulatory oversight is likely to still be very high. This is mainly due to the high degree of standardization, which is needed to coordinate the overall system.

The golden mean? Norway, Belgium and the Netherlands are combining two models

The evaluation above shows that each model for data management in smart grids has is strengths and weaknesses. Many European States apply or are planning to apply the Central Data Hub concept. In the cases of Norway, Belgium and the Netherlands the CDH concept is combined with the DSO as market facilitator idea: either the TSO or several DSOs together have the responsibility to operate the data management system for smart metering. By combining the two models CDH and DSO as market facilitator, most of the criteria we discussed in this post can be addressed quite well. Therefore, it seems that the combination of the models is the right way to go.

What do you think? Do you have another perspective, additional criteria, which we should take into account? If so, we are looking forward to your comment and to discuss with you.

Source: energycollective

< Back to all entries